[:es] OTROS LIMITES

OTROS LIMITES

Revista Basa (Julio 1993)

Domingo Díaz utiliza la escultura para aproximarse, con diferentes términos, a disciplinas que mantienen una estructura propia, lo que se quiere decir es que si queremos valorar un lenguaje, hay que emplear un segundo lenguaje que posea cierta conexión con el pero sin disponer de sus propias claves.

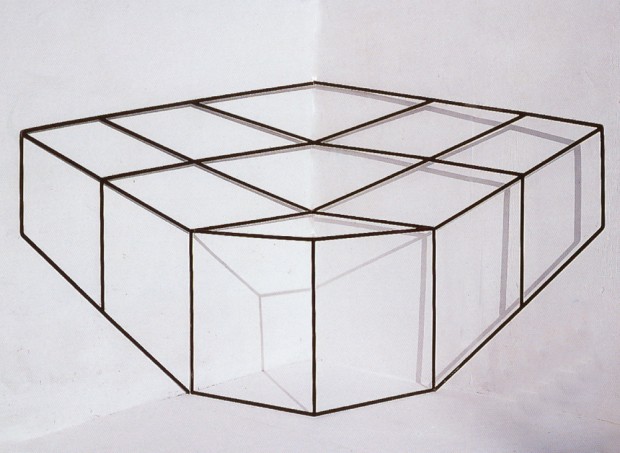

Estos ámbitos cercanos son principalmente del dibujo y la arquitectura. Sus esculturas buscan una frontera difusa pero común a estos distintos espacios artísticos. Es precisamente esta aproximación la que le permite afianzarse en el lenguaje más intrínseco de la escultura. Aunque esto pueda parecer paradójico, es perfectamente explicable utilizando la fotografía como catalizador. Al fotografiar su serie de proyecciones, la película registra una realidad difícilmente comprensible. Lo que parece ser la perspectiva dibujada de un volumen, es una pieza cuyo volumen se corresponde con esa perspectiva. Esto desliga la escultura de Domingo Diaz de reminiscencias pictoricistas. Es decir, no se trata de una realidad fotografiable o “pintoresca”, atendiendo a la etimología de esta última palabra. Es indispensable moverse delante de cada una de estas piezas para poder comprender esta realidad engañosa.

Ninguna obra de Domingo Díaz pretende ser un cuadro. Es imposible tener un punto de vista único sobre cada una. No es, por tanto, una cosa en si sino un proceso de relaciones infinitas que trabajan sobre un espacio físico. No se mira pues a una escultura ubicada en un espacio sino más bien el espacio a través de ella. Se trata de piezas carentes de direcciones jerarquizadas, de puntos de vista principales, en provecho de una errancia espacial compleja en la cual los objetivos no han sido revelados.

En una primera lectura de la obra es fácil caer en la vinculación de esas piezas con las perspectivas engañosas del Barroco. En una reflexión más profunda se observa que en estas esculturas se produce una negación del planteamiento Barroco y una vinculación más estrecha con la obra de Pironesi. De hecho, el Barroco dirigía al espectador hacia un climax final después de un recorrido cuyo último objetivo era conocido. En la obra de Pirenesi se produce la ruptura entre el espacio barroco y lo que se puede considerar el espacio moderno. En el Barroco el orden es rígido y la libertad es ilusión, por tanto, no es en absoluto el antecesor del espacio moderno sino que es éste su negación. La obra de Domingo Díaz no está orientada hacia un fin, el centro está en movimiento o al menos desplazado.

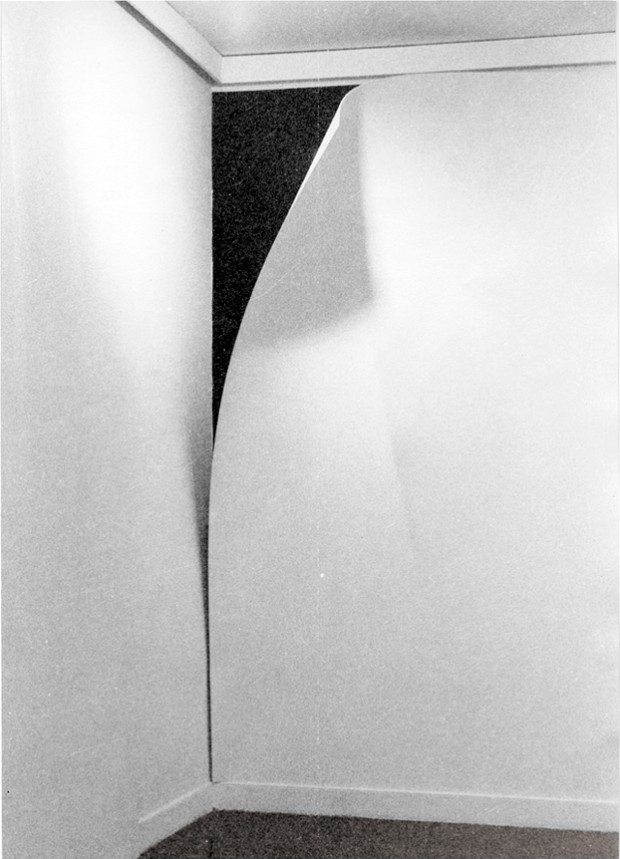

Michel Fied nos plantea que lo que distingue radicalmente la esculturas minimalistas de las obras del movimiento moderno es la ausencia de determinación a priori de sus límites. Aunque la escultura de Diaz no se puede calificar de minimalista, si tiene en común esta carencia de limites. Lo que me resulta más innovador en la obra de Domingo Díaz es la capacidad para hacer participe al entorno en sus esculuras. Podemos cogerlas, llevarlas bajo el brazo pero carecen de sentido hasta estar instaladas en un esquina o en una pared. Es entonces cuando extiende su influencia a todo el paramento e incluso al suelo. En ese momento es imposible acotar la obra, ponerle limites o quizás, simplemente, los limites son otros.

Cuatro series interrelacionadas integran sus últimos trabajos: “Esquinas”, “Paredes”, “Proyecciones” y “Fugas”. En ellas se juega con una dialéctica de inversiones y presentan una nota discordante respecto a las referencias del espectador en torno a los marcos eternos e inamovibles de los parámetros que configuran loa habitáculos donde se desarrolla la mayoría de las actividades vitales.

Su conexión con la arquitectura es estrecha. Solo hay que echar un vistazo a los proyectos del grupo americano SITE para encontrar paralelismos formales, aunque conceptualmente partan de premisas diferentes. En ambos hay algo de ironía y sin duda ciertas dosis de humor.

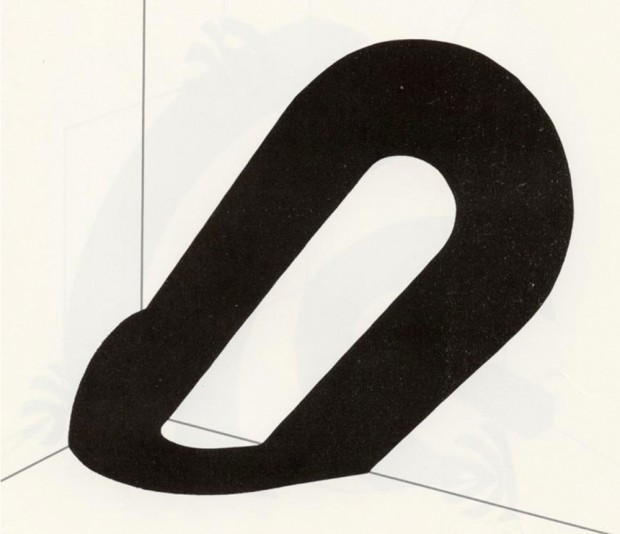

En “Paredes” intenta crear una ilusión óptica en la que el espectador cree ver lo que hay tras la pared. La sorpresa llega al aproximarnos y lo que parece ser un vacio oscuro no es más que una pieza superpuesta en el muro. Sin embargo la paradoja no deja de ser efectiva e irónica. Una clara referencia al Pop se manifiesta en “Abertura”, donde una gran llave abrelatas resulta ser el mecanismo más adecuado para “abrir una ventana”, mientras en “Arañazos” podemos imaginar perfectamente el chirrido que provocaron las uñas al arañar la pared.

Estas piezas surgen de una serie de estudios realizados a partir de la propia geometría y de la propia esencia de los objetos. Así como la geometría es un primer intento de controlar las formas naturales, con los signos se pretende no sólo la racionalización sino incluso la abstracción del Universo como el paso final de los científico.

La obra de Domingo Díaz plantea una serie de cuestiones sobre la relación entre las distintas facetas del arte y nos da a conocer esos espacios fronterizos aún sin explorar del todo, donde pintores, escultores y arquitectos, que trabajan en la actualidad, tienen un gran campo para la investigación.

Basa magazine

Text: Clara Muñoz

Domingo Díaz, reflections about his work.

Domingo Díaz uses sculpture to approach himself, with different terms and disciplines that maintain a structure. That means that if we want to value a language, we have to use a second language with some connections with the first but without its own clues.

These close spheres are mainly drawing and architecture. His sculptures look for a vague but common borderline to these different artistic spaces. Precisely, this proximity allows holding onto the most intrinsic language of sculpture. Although it can seem paradoxical, it can be explained by using photography as an agent of change. When he takes photos of his projections, the movie records a hardly understandable reality. What seems to be a drawn perspective of a volume is a piece whose volume doesn’t correspond to that perspective. That separates Domingo Díaz’s sculpture from pictorial reminiscences. That means that is not about a “picturesque” reality, according to the etymology of that word. It is necessary to move in front of each work to understand this deceptive reality.

No Domingo Díaz’s work pretends to be a picture. It’s impossible that we can have only one point of view. It’s not, therefore, a thing itself but a process of endless relationships that work on a physical space. You don’t observe a sculpture in a space but the space through the sculpture. They are pieces without directions organised in a hierarchy, without main points of view to the benefit of a complex and spatial vagrancy in which the objectives haven’t been revealed.

At first reading of the work, it’s easy to think about the link of pieces with fake perspectives of Baroque. With a deeper reflection we can observe a denial of Baroque’s approaches and a narrower link with Piranesi’s work. In fact, Baroque leads the spectator to a final climax after a walk whose last aim was known. In Piranesi’s work, a breakdown is produced between Baroque’s space and modern space. In Baroque, the order is rigid and freedom is an illusion, so, it’s not absolutely the ancestor of modern space but its denial. Domingo Díaz’s work isn’t orientated towards an end, the center is in motion or, at least, out of place.

Michael Fied suggests that what really distinguishes minimalist sculptures from works of modern movements is the lack of determination on its limits. Although Díaz’s sculpture can’t be described as minimalist, it has that lack of limits. I believe that the most innovating thing in Domingo Díaz’s work is the ability to play with the environment with his work. We can take them, carry them, but they have no sense without a wall or a corner. From that point on, they spread out their influence to the whole surface even the floor. In that moment is not possible to enclose or put limits on the work for maybe, the limits are now different.

Michael Fied suggests that what really distinguishes minimalist sculptures from works of modern movements is the lack of determination on its limits. Although Díaz’s sculpture can’t be described as minimalist, it has that lack of limits. I believe that the most innovating thing in Domingo Díaz’s work is the ability to play with the environment with his work. We can take them, carry them, but they have no sense without a wall or a corner. From that point on, they spread out their influence to the whole surface even the floor. In that moment is not possible to enclose or put limits on the work for maybe, the limits are now different.

His latest work consists of four interrelated series: “Esquinas” (“Corners”); “Paredes” (“Walls”); “Proyecciones” (“Projections”) and “Fugas” (“Leaks”). These series play with dialectics made of inventions and present a discordant note, with regard to the spectator’s references, about eternal and immovable frames of surfaces that configure spaces where vital activities are carried out.

He has a very close connection with architecture. We only need to have a look to the projects of the American group SITE to find formal parallelism although, conceptually, they come from different premises. Both of them have irony and, with no doubt, some doses of humor.

In “Paredes” (“Walls”) he tries to create an optical illusion where the spectator believes they see what is behind the wall. The surprise comes when we get closer and what seems to be a dark void is only a superimposed piece on the wall. However, the paradox is effective and ironic. We can see a clear reference to Pop in “Abertura” (“Opening”) where a big key is the most appropriate mechanism to “open a window”, whereas in “Arañazo” (“Scratch”) we can perfectly imagine the squeak made by the nails that scratch the wall.

These pieces appear from a series of studies carried out from the geometry and essence of the objects. Geometry is a first attempt to control natural forms but signs try not only rationalisation but the abstraction of the Universe as the final step of the scientific.

Domingo Díaz’s work suggests a series of questions about relations between different parts of art and reveals those border spaces, not entirely explored, where painters, sculptors and architects who work nowadays, have a big field to investigate.

[:]